November, 2009

Sometimes people get so excited about the idea of enhanced greenhouse they rush to propose "cures". Have a look at this one:

Forests in the desert: the answer to climate change?

Climate change could be cancelled out in a staggeringly ambitious plan to plant the Sahara desert and Australian outback with trees

One day, this could all be trees … a recent scientific paper claims that turning deserts into forests is the best way forward. Photograph: Guido Cozzi/Corbis

Some talk of hoisting mirrors into space to reflect sunlight, while others want to cloud the high atmosphere with millions of tonnes of shiny sulphur dust. Now, scientists could have dreamed up the most ambitious geoengineering plan to deal with climate change yet: converting the parched Sahara desert to a lush forest. The scale of the ambition is matched only by the promised rewards – the scientists behind the plan say it could "end global warming".

The scheme has been thought up by Leonard Ornstein, a cell biologist at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, together with Igor Aleinov and David Rind, climate modellers at Nasa. The trio have outlined their plan in a new paper published in the Journal of Climatic Change, and they modestly conclude it "probably provides the best, near-term route to complete control of greenhouse gas induced global warming".

Under the scheme, planted fields of fast growing trees such as eucalyptus would cover the deserts of the Sahara and Australian outback, watered by seawater treated by a string of coastal desalination plants and channelled through a vast irrigation network. The new blanket of tree cover would bring its own weather system and rainfall, while soaking up carbon dioxide from the world's atmosphere. The team's calculations suggest the forested deserts could draw down around 8bn tonnes of carbon a year, about the same as emitted from fossil fuels and deforestation today. Sounds expensive? The researchers say it could be more economic than planned global investment in carbon capture and storage technology (CCS).

"The costs are enormous but the scale of the problem is enormous," says Ornstein, who is best known for pioneering a cell biology technique called polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the 1950s. "It's a serious suggestion in that I believe it is the most promising and practical option in terms of current technology to solve the biggest parts of the problem."

The scheme could cost $1.9tn a year, he says. "When that's compared to figures like estimates of $800bn per year for CCS, our plan looks like a loser. But CCS can address only about 20% of the problem at the $800bn price. Mine addresses the whole thing. And CCS would involve a network of dangerous high-pressure pipelines coursing through the most developed neighbourhoods of our civilisations, compared to relatively benign water aqueducts in what are presently virtually uninhabited deserts." (David Adam, The Guardian, Nov. 4, 2009)

The above is based on this Irrigated afforestation of the Sahara and Australian Outback to end global warming in Climatic Change -- it's open access so you can download the .pdf and view the supplemental movies.

Sounds great, doesn't it? Most everyone loves trees and who wouldn't like to see the deserts bloom again? But could it work? Or, more importantly, would it work as advertised?

In short, no. Their stated calculation is that "the forested deserts could draw down around 8bn tonnes of carbon a year, about the same as emitted from fossil fuels and deforestation today", so it couldn't reduce enhanced greenhouse effect, only slow its growth (just ignore all the energy requirement for that amount of desalination, earthworks and construction...).

Worse, it's inappropriately based on regional simulations performed with GISS ModelE, with its listed global shortcomings:

Principal Model Deficiencies

ModelE [2006] compares the atmospheric model climatology with observations. Model shortcomings include ~25% regional deficiency of summer stratus cloud cover off the west coast of the continents with resulting excessive absorption of solar radiation by as much as 50 W/m2, deficiency in absorbed solar radiation and net radiation over other tropical regions by typically 20 W/m2, sea level pressure too high by 4-8 hPa in the winter in the Arctic and 2-4 hPa too low in all seasons in the tropics, ~20% deficiency of rainfall over the Amazon basin, ~25% deficiency in summer cloud cover in the western United States and central Asia with a corresponding ~5°C excessive summer warmth in these regions. In addition to the inaccuracies in the simulated climatology, another shortcoming of the atmospheric model for climate change studies is the absence of a gravity wave representation, as noted above, which may affect the nature of interactions between the troposphere and stratosphere. The stratospheric variability is less than observed, as shown by analysis of the present 20-layer 4°x5° atmospheric model by J. Perlwitz [personal communication]. In a 50-year control run Perlwitz finds that the interannual variability of seasonal mean temperature in the stratosphere maximizes in the region of the subpolar jet streams at realistic values, but the model produces only six sudden stratospheric warmings (SSWs) in 50 years, compared with about one every two years in the real world. ... Climate simulations for 1880-2003 with GISS modelE -- Hansen et al. 2007, in press. (that link is stale but the deficiencies remain current from the most recent listing viewed)

As yet there is exactly zero evidence running regional simulations in GCMs has any prognostic value whatsoever. And yes, I'm cheating to some extent since models are renowned for being unable to accurately reproduce cloud formation and precipitation, being less accurate than a table of random numbers at regional scales, so I knew before opening the document they had next to no chance of getting the numbers close to real world values.

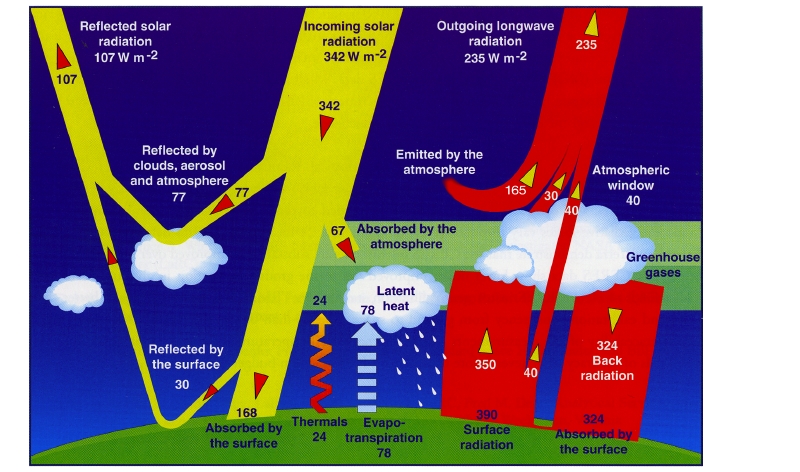

You've seen Earth's energy budget before, just for a change we've given you a more colorful version of Kiehl and Trenberth, just remember these numbers are averaged across all latitudes:

Very pretty, you say, but what's that got to do with a scheme to forest the Sahara? A fair bit really, let's look at a couple more pretty pictures before we break down a few numbers. Firstly, let's consider albedo -- the amount of incoming solar shortwave radiation (ISR) reflected back to space:

NASA images courtesy Takmeng Wong and the CERES Science Team at NASA Langley Research Center

Observant readers will immediately note that the bright Sahara, Sahel and Saudi Arabian Peninsula reflect a staggering amount of solar radiation back to space. Oceans and forested areas, not so much and in fact these regions have very low albedo compared with deserts and particularly thick, low cloud and ice and snow fields in summer season.

Another point to note is the usual Mercator Projection trap for the unwary embedded in the above projections: distortion of scale. Polar regions and Greenland do not really reflect the vast amount of ISR the casual viewer could expect from the above graphics, more realistic area representation is found in Sinusoidal:

or Mollweide projections:

| Relative areas compared - Equatorial aspect | ||

| Mercator | Greenland | |

| Africa | ||

| Mollweide and Earth |

Greenland | |

| Africa | ||

You can read all about the wonderful world of Cartographical Map Projections on Carlos A. Furuti's site. The table at right comes from there and gives you an idea of scale distortion involved. Rather than being larger than the Sahara Greenland is in fact smaller than the Saudi Peninsula.

OK, that's one small problem because, referring to Kiehl and Trenberth above, Earth's average surface albedo is listed as a mere 30 Watts per meter squared (W/m2) or about 8.8%, which is fair enough because seven-tenths of the planet's surface is water and that has very low albedo. The Sahara though is one bright desert, easily topping the average 15-40% albedo for arid regions while evergreen forests range from a lowly 5-15%. Even if the irrigated forests encouraged 40% cloud cover (the global average) and these clouds were perfect 100% reflectors there still couldn't be a decrease in absorbed ISR. I average it like this:

700 W/m2 * 0.4 (near-perfect reflection from 40% cloud) = 280 W/m2 averaged over the whole area +

300 W/m2 * 0.6 (unclouded balance of region) * 0.3 (approximate ratio of forest:desert albedo) = 54 for a

net average of 334 W/m2. No improvement there over the native desert state indicated by CERES.

Just to run the global average numbers so there's no doubt, clouds, dust and other aerosols and atmospheric scattering combined account for about 77 W/m2 or 22.5% ISR while the CERES graphics show the Sahara as reflecting roughly 5 times that. Moreover, irrigation and forestation will inevitably reduce the dust sourced from the Sahara and Central Australia that is part of the listed atmospheric albedo and which supplies iron to the iron-starved oceans, feeding the algal blooms that draw down atmospheric carbon dioxide and providing the basis for the oceanic food chain.

No cooling there for their trifling annual price tag of $1,900,000,000,000 (1.9 trillion dollars) and some potential downsides beginning to appear (just imagine if someone wanted to deliberately discolor the Arctic summer sea ice and Greenland, which together amount to similar albedo as the Sahara).

Update: my use of K&T 1997 for energy balance calculations may be more problematic than first realized. I see no reason to doubt this communication in one of the released CRU e-mails:

... http://junksciencearchive.com/FOIA/mail/1255523796.txt

On Oct 14, 2009, at 10:17 AM, Kevin Trenberth wrote:

Hi Tom

How come you do not agree with a statement that says we are no where close to knowing where energy is going or whether clouds are changing to make the planet brighter. We are not close to balancing the energy budget. The fact that we can not account for what is happening in the climate system makes any consideration of geoengineering quite hopeless as we will never be able to tell if it is successful or not! It is a travesty!

Kevin [em added]

That's this Kevin Trenberth: http://www.cgd.ucar.edu/cas/trenbert.html of Kiehl & Trenberth (1997) energy balance fame, with subsequent revisions.

Obviously that could seriously upset my calculations but apart from understating the potential percentage increase in local greenhouse effect there's no apparent problem (it could easily increase local GHE by 150% by moistening the atmosphere, although the IPCC's +3 °C for 2xCO2 still appears overstatement by a factor of 4). The CERES data should not be affected by Trenberth's admission that we can not model energy balance since that is empirical data, not modeled make-believe. Either way holding atmospheric carbon dioxide steady, as they claim their proposal could do, and increasing the proportion of wet tropical atmosphere is no way to reduce net greenhouse effect. :End update

What's that? You like forests better than deserts and think addressing global warming is urgent? Well we think vegetated regions are nicer too but hang on, we haven't finished the temperature calculations from this little fantasy just yet. They write blithely of towering 100m Eucalyptus grandis -- in sand dune country?

Sorry guys, simply not compatible with the relatively shallow soil moistening proposed, these tall (and thirsty) trees have a deep reach. Below is more what you could achieve:

Forest savanna as could be established in the Sahara.

One thing about desert atmospheres that most people can agree on is that they tend to be rather dry and short on cloud cover, which is why they lack much of the greenhouse effect responsible for reducing nocturnal cooling and keeping minimum temperatures from plunging overnight in moister regions. It is theoretically possible for carbon dioxide (CO2) to capture almost 40% of outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) although this is based on a bit of a trick -- it relies on a theoretical nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) atmosphere and a total absence of all other greenhouse gases. In the real world CO2 is thought to account for about 5% of tropospheric greenhouse effect while water vapor and clouds account for 95% (S.M. Freidenreich and V. Ramaswamy, “Solar Radiation Absorption by Carbon Dioxide, Overlap with Water, and a Parameterization for General Circulation Models,” Journal of Geophysical Research 98 (1993):7255-7264.).

In the Sahara then we have greenhouse effect from CO2 plus a lower than global average contribution from water vapor and clouds, all delivering relatively low net greenhouse effect and these guys want to irrigate and forest areas totaling roughly 10 million kilometers squared (10,000,000 Km2), moistening the desert air with increased evapotranspiration and consequently significantly increasing regional greenhouse effect.

Referring back to the energy budget above and using global average figures, CO2 probably delivers at minimum 324 x 0.05 = 16.2 W/m2 downwelling longwave radiation (DLR) and could possibly manage 40% or 324 x 0.4 = 129.6 W/m2 in a totally dry atmosphere. Theoretically OLR capture by water in its various forms could be increased in the desert from its current relatively low level to 95% or 307.8 W/m2, which means reducing some of CO2's listed effect but still delivers a 60% net increase in total greenhouse effect. Hot desert air can have high absolute humidity (and does by the Mediterranean Coast, for example) but across the regions targeted for forestation this is more the exception than the rule.

Exactly how much greenhouse increase is involved? That's difficult to say since basic data is missing but given the increase in potential cloud cover and moisture availability it could be 60% or 205 W/m2 (it would be silly to assume less than 40% or about 130 W/m2). Over approximately 10 million Km2 that equates to about 4 W/m2 over the whole planet. In turn that is the same as the IPCC's guesstimated increased forcing for a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide, which will allegedly yield +3 °C global warming, just as could be expected from this über expensive cooling scheme (the lower bound estimate of 40% would equate to 1.8 °C global warming). Not exactly as advertised, is it?

It's all very well for us to hypothesize and guesstimate on this but is there any support for irrigation-driven warming in the literature?

Yes, in fact there is. John Christy and Bill Norris have published on the topic. Here's a link to the UAH press release: "Irrigation most likely to blame for Central California warming" and you'll find a .pdf of their paper here.

Irrigating deserts might be desirable for any number of reasons but cooling the planet should not be one of them. And this doesn't even consider the energy and engineering costs of their little scheme, which they cost at about a buck a gallon of gas -- based on information from Wikipedia, no less...

If enhanced greenhouse is really a problem (and we see no evidence that it might be) then increasing net global greenhouse effect and warming the planet by moistening the atmosphere in the dry regions of the highly irradiated 0-30 degree latitude band is no way to cool the world, is it? In fact reducing something by making it larger is about the stupidest method proposed yet and they only want to spend 1.9 trillion dollars every year for the foreseeable future to do so.

Environmental remediation is pretty cool but planetary air conditioning is not the reason to do it. "Cooling" the planet by heating it is a really stupid idea.

PlayStation® climatology... Sheesh!